Lucado finds peace in quiet providence amid personal struggles

SAN ANTONIO (RNS)—Pastor and bestselling author Max Lucado believes the story of Esther can help guide Christians through challenging times.

Lucado should know.

The biblical book bearing Esther’s name has helped him through his own bout with a breakthrough case of COVID-19 and his recent diagnosis with a serious health condition, called an ascending aortic aneurysm.

Not to mention the national upheaval of a pandemic, a reckoning over racial justice, a rancorous presidential election and a siege of the U.S. Capitol, all in the past year.

During that time, Lucado, teaching pastor at Oak Hills Church in San Antonio, created daily Coronavirus Check-In videos online and saw a bump in sales of his books, with titles like Anxious for Nothing and Unshakeable Hope.

He also unpacked the story of Esther, the Jewish queen who saves her people from genocide in the biblical account, for his latest book, You Were Made for this Moment: Courage for Today and Hope for Tomorrow.

“The theme of the book of Esther, indeed, the theme of the Bible, is that all injustices of the world will be turned on their head,” he writes in You Were Made for this Moment.

“When we feel like everything is falling apart, God is working in our midst, causing everything to fall into place. He is the king of quiet providence … and he invites you and me to partner in his work.”

Lucado spoke with Religion News Service about You Were Made for this Moment, the book of Esther and his recent diagnosis. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

What made you decide to write about Esther?

As 2020 kicked off, I was just like everybody else—just really pushed back on my heels with all the struggles of the spring of 2020. I was actually scheduled to teach a series at our church on stewardship, but that seemed really tone deaf. Everybody was just reeling from the pandemic and the stress and insecurity and fear.

So I recalibrated and began thinking, “Is there a series in the Bible that deals with a global calamity?” Of course, they’re all over the place. I’d already preached through Joseph, already preached about Exodus, but I’d never taught on the life and the story of Esther. I’ve always wanted to. I’ve loved that story for all my life. So I said, “OK, we’re going to study through this as a church,” and it really resonated because it is a story of a global calamity, at least in terms of the Hebrews. They had no out. It was just overwhelming. It seemed like there was no solution, and then God turned it around in the story and provided deliverance.

How did writing You Were Made for this Moment during the COVID-19 pandemic and other upheavals this past year and a half impact how you read and thought about the book of Esther?

I don’t think I was aware how the two main Hebrew characters, Mordecai and Esther, were really clandestine in their faith initially. They blended into the culture, and they were happy to be thought of as Persian. They were so Persian, he could work for the king and she could sleep with the king, and nobody knew they were Jewish.

I don’t think I was aware how the two main Hebrew characters, Mordecai and Esther, were really clandestine in their faith initially. They blended into the culture, and they were happy to be thought of as Persian. They were so Persian, he could work for the king and she could sleep with the king, and nobody knew they were Jewish.

In the day in which we live, it seems more difficult to know how to live a Christian life and not be a jerk, on one extreme, or not be invisible, on the other extreme. How can I lead a Christian life in which I have a deeply rooted faith and yet still be a great neighbor, still be good for society, still not be that person that people roll their eyes at—that we really are the constructive force for good in the world?

The other is just the fear the Jewish people must have felt. The king of Persia was a misogynist, partying, oblivious, clueless—more of a drinker than a thinker kind of guy—and then his righthand man (Haman) just decided to annihilate all the Jews. Remember these are exiles. These are marginalized people. So if you’re a Hebrew in those days, you really feel outmaneuvered by fate, outnumbered by your foes.

I think the pandemic left people feeling weary, worried and wounded by the uphill battle, and I think it’s still going on. I remember when I presented this book to the publisher, I said, “Unfortunately, this would have been great to release it in the beginning of the pandemic,” because when I presented it, I thought the pandemic was ending. We all did. And now it’s still going on.

Why do you believe Esther’s story can guide readers through challenging times—not just pandemics and politics, but the personal struggles that have continued during this time, too?

I think we are so mesmerized by stories in Scripture that are dramatic, like the splitting of the Red Sea or the raising of the dead. Those stories are extraordinary and inspirational.

But the story of Esther is interesting because there’s no visible miracle. The reality of their world is kind of like the reality of ours; that is, most of us don’t experience those dramatic miracles. The theology behind Esther is quiet providence. It’s kind of behind the scenes. Esther’s famous for being one of two books in the Bible, along with Song of Solomon, in which the name of God does not appear.

I think the relevancy of the story to our day is most of us don’t have these dramatic miracles, but we can—by virtue of this story and others—trust the behind-the-scenes work of God in the middle of our challenge.

You’ve faced your own personal struggles. You recently announced you’d been diagnosed with an ascending aortic aneurysm. Any update on your health?

We were really caught off guard by this because I’m in good health. It’s asymptomatic. But I was actually having a calcium test done, and in the process of the calcium test, it became clear to the doctor that I have this aneurysm. It’s pretty sizable. Since I announced it, I have come to learn it’s just shy of being large enough where surgery is mandatory. It’s an option right now, so we’re still doing tests.

Initially, I had about three or four days in which I felt like I couldn’t get my emotions under control. I kept thinking: “Oh man, I’ve got this ticking time bomb in my chest. It’s going to rupture at any moment.” But I’ve really felt peaceful.

You had a breakthrough case of COVID-19 two months ago, too.

Boy, I did, and it knocked me off my feet. I thought I had dodged the bullet because I was vaccinated, but it knocked me down for about three days. I really was sick. But then, I got over it. I’m thankful I was vaccinated. I think that helped it from ever getting into my lungs. I was sick—so sick I could hardly get off the couch, and my wife would only see me wearing a hazmat suit. But we made it.

How has what you took from studying the book of Esther helped you through your own challenging times?

There were times, especially with the surfacing of the aneurysm story, I was so thankful I had just spent the last month looking at a great story of God’s providence because it gave me some tools in my tool chest to go to.

Number One, I had this great story of Esther that was really fresh in my mind.

Number Two, I was really reacquainted with some of the promises in Scripture that mean so much to us. Romans 8:28—“Everything works together for the good of those who love him and are called according to his purpose”—gave me a Scripture upon which to meditate. Also, Philippians 4—that there is a “peace that passes understanding.” I came to experience that peace. In fact, I think I have that peace even to this day.

I probably should be more worried than I am, but I just really feel peaceful about it.

What do you hope readers will take away from the book?

In the story of Esther, Mordecai eventually discloses he is a Jew … and then he sends a message to Esther that relief and rescue will come, and who knows but you have been placed in this position for such a time as this? I think that’s a message all of us can receive.

If God truly is sovereign, if we’re truly under his provision, if there is a good God overseeing all the affairs of mankind, then he has placed you and me on the planet at this time for some reason. Being faithful to him during a time like this is really our highest call. None of us would have chosen to have to live through a pandemic. Nobody wants to live through the World War. Nobody wants to live through the holocaust of Haman. But we don’t get that choice.

We are called to live out our faith during tough times. In these days of politics and pandemic, in which people can be so angry at each other and so easily triggered, we really need a quorum of people who will do their best just to live out their faith and make each neighborhood a better place.

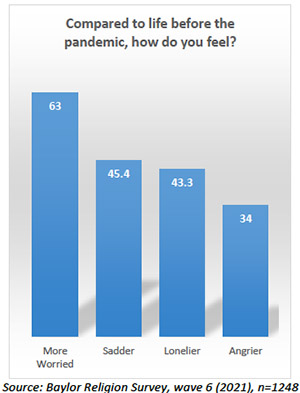

Across four emotions—worried, sad, lonely and angry—more than one-third of Americans reported feeling these emotions more strongly compared to before the pandemic. This pattern particularly was apparent for feeling worried, especially for parents with children living at home.

Across four emotions—worried, sad, lonely and angry—more than one-third of Americans reported feeling these emotions more strongly compared to before the pandemic. This pattern particularly was apparent for feeling worried, especially for parents with children living at home.

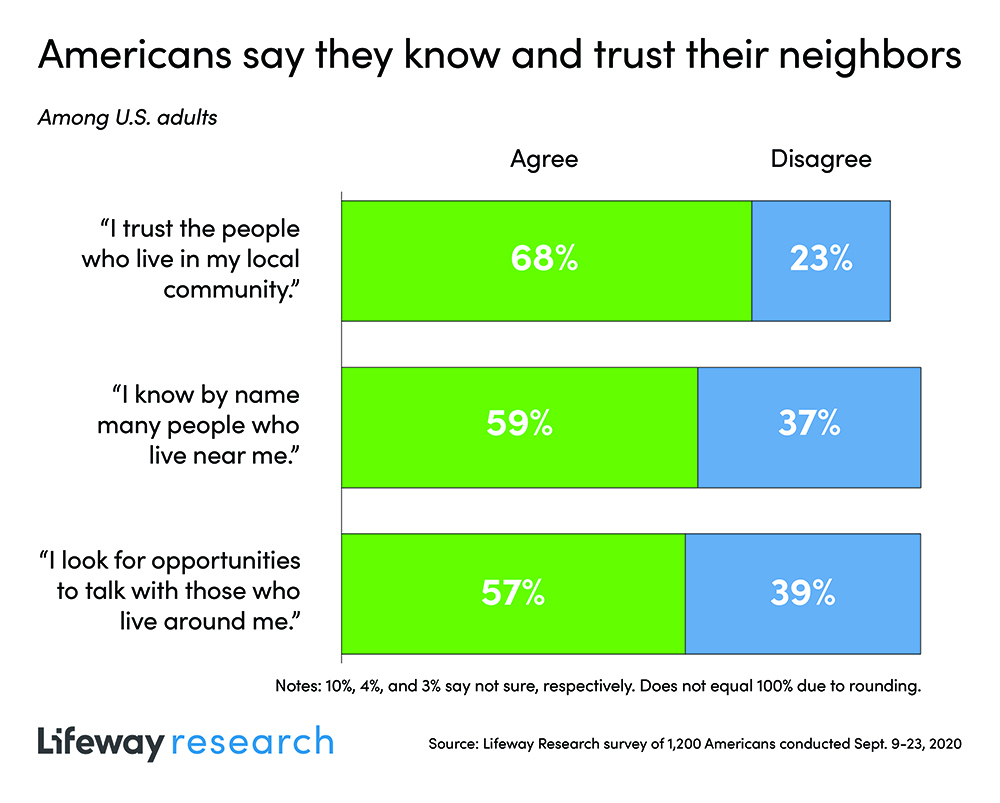

Men (72 percent) are more likely than women (63 percent) to say those who live around them are trustworthy. Those 65 and older are most likely to agree (79 percent), while younger adults, aged 18-34, are least likely to agree (59 percent).

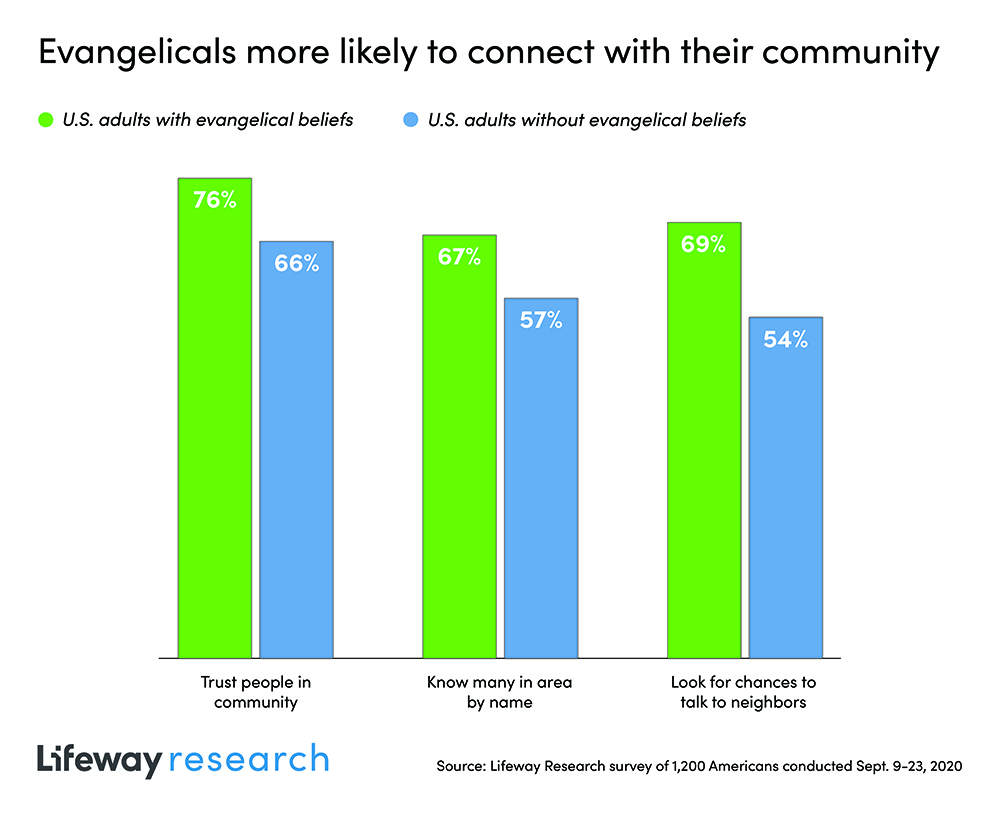

Men (72 percent) are more likely than women (63 percent) to say those who live around them are trustworthy. Those 65 and older are most likely to agree (79 percent), while younger adults, aged 18-34, are least likely to agree (59 percent). Christians who attend church at least monthly (71 percent) are more likely than those who attend less frequently (51 percent) to look for opportunities to talk to those who live around them. Those with evangelical beliefs (69 percent) are also more likely than those without such beliefs (54 percent) to want those times of discussion.

Christians who attend church at least monthly (71 percent) are more likely than those who attend less frequently (51 percent) to look for opportunities to talk to those who live around them. Those with evangelical beliefs (69 percent) are also more likely than those without such beliefs (54 percent) to want those times of discussion.

“For many Americans, circumstances in 2020 led to an increased focus on their fears,” said Scott McConnell, executive director of Lifeway Research. “Many feared getting COVID; others feared social unrest during protests; and politicians played on people’s fears in ads and speeches.”

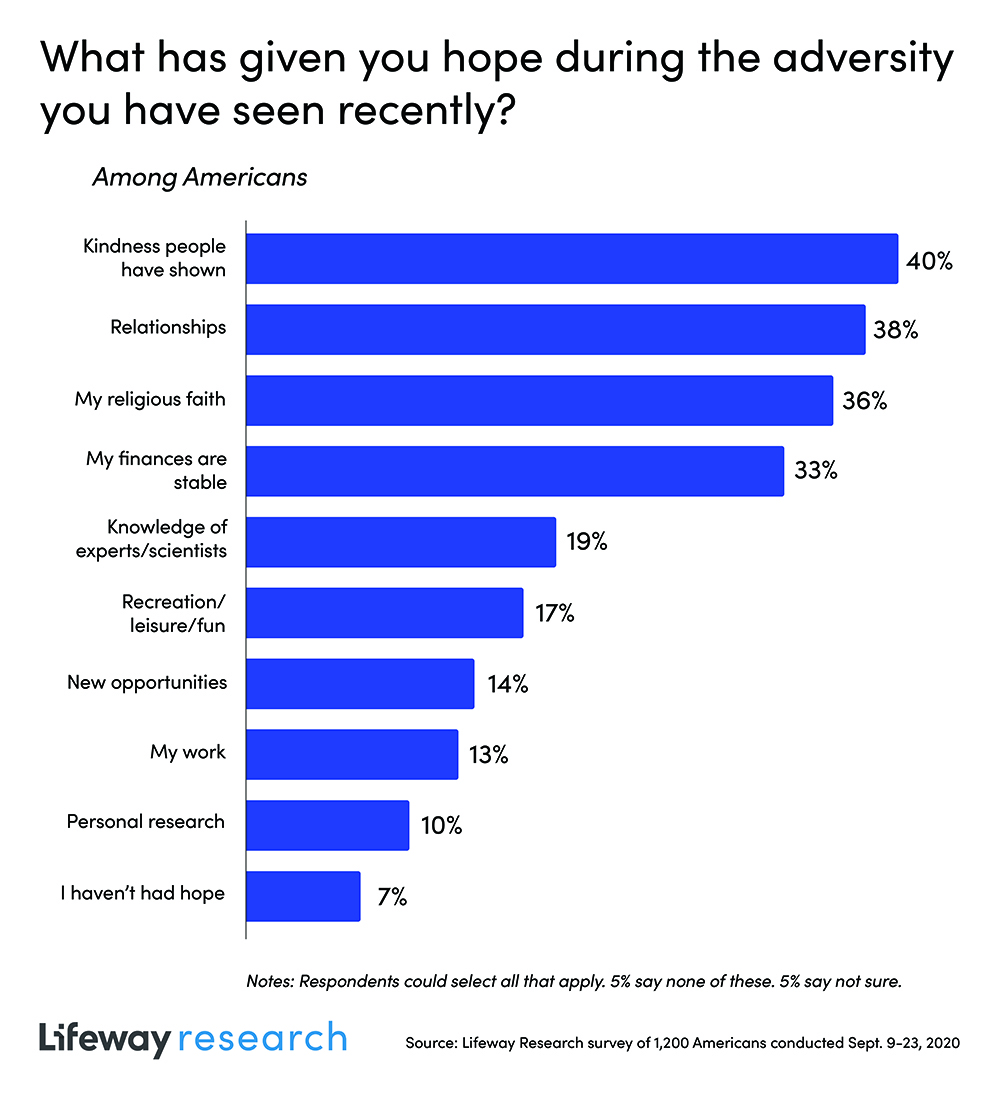

“For many Americans, circumstances in 2020 led to an increased focus on their fears,” said Scott McConnell, executive director of Lifeway Research. “Many feared getting COVID; others feared social unrest during protests; and politicians played on people’s fears in ads and speeches.” The top source of hope for U.S. adults through 2020 is the kindness people have shown (40 percent), followed closely by relationships (38 percent), their religious faith (36 percent), and their finances being stable (33 percent).

The top source of hope for U.S. adults through 2020 is the kindness people have shown (40 percent), followed closely by relationships (38 percent), their religious faith (36 percent), and their finances being stable (33 percent). While Americans overwhelmingly say they get the most satisfaction from doing the right thing, they’d much rather eliminate anxiety from their lives than wrongdoing.

While Americans overwhelmingly say they get the most satisfaction from doing the right thing, they’d much rather eliminate anxiety from their lives than wrongdoing.