WACO—Chronic hunger has decreased globally in recent years, but armed conflict has increased the prevalence of acute hunger, the chief of the United Nations’ food-assistance and humanitarian agency said.

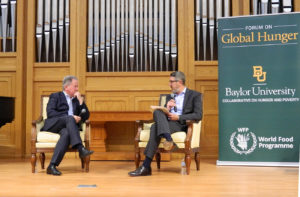

When he became executive director of the World Food Programme in 2017, “80 million people were marching toward starvation,” David Beasley told a crowd at Baylor University’s Truett Theological Seminary on Sept. 10.

That number rose to 135 million at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, he added.

Beasley pointed to three causes of acute hunger: “Man-made conflict, and I emphasize the gender; global climate extremes; and fragile governance.”

Use food to wage peace

But just as food often is used as a weapon of warfare—and as a recruitment tool for terrorists—he insisted it can be used as a powerful tool “for defusing explosive situations.”

“We can end hunger by 2030, but it won’t happen unless we end man-made conflict,” Beasley told participants at the Forum on Global Hunger, sponsored by the Baylor Collaborative on Hunger and Poverty.

“My goal is to put the WFP out of business” by making peace, eliminating hunger and promoting self-sufficiency, he asserted.

“Food brings peace. Hunger brings conflict and destabilization,” he said.

Last year, Beasley addressed the U.N. Security Council, warning members the world was teetering “on the brink of a hunger pandemic” at the same time it faced the COVID-19 pandemic.

Sign up for our weekly edition and get all our headlines in your inbox on Thursdays

Unless the international community intervened, he predicted the number of starving people could approach 270 million by the end of 2020. International leaders responded, and the most severe possible outcome was averted.

Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, the WFP not only delivered food around the globe, but also served as the hub for transporting life-saving medical equipment at times when the supply lines and delivery systems were disrupted.

For its efforts to combat hunger, create conditions for peace in areas affected by conflict and “prevent the use of hunger as a weapon of war and conflict,” the WFP received the 2020 Nobel Peace Prize.

See each person as created in God’s image

Beasley, former governor of South Carolina, spoke to the issues of making peace and fighting hunger from his own Christian faith. He began his address at Baylor by quoting the words of Jesus in Matthew 25: “Whatever you have done to the least of these, you have done it to me.”

As a Christian, Beasley said, he has been able to appeal to other Christians, Muslims and even atheists to recognize the wisdom of the command in both the Hebrew and Christian Scriptures: “Love your neighbor as yourself.”

In fact, he learned from a Jewish scholar assigned to the Vatican that an alternative translation from Leviticus is “love your neighbor as your equal.” Beasley said he interprets that command as being grounded in the reality that all people are equal because every individual is made in God’s image.

“Even the worst of the worst is created in the image of God,” he said.

So, in his work with WFP, Beasley seeks to appeal to the God-given desire to help people—at least their own people—that exists even among warlords and terrorists.

“We meet with bad guys in bad places,” negotiating for access to deliver food to people in critical situations, he said.

When asked in an interview after his public presentation how he makes peace with difficult people, Beasley suggested: “Be honest. Don’t play games. Speak from the heart. You’ve got to listen and take the time to let them share. That’s how you develop relationships that impact the hearts of leaders—sit down, break bread, and build trust.”

We seek to connect God’s story and God’s people around the world. To learn more about God’s story, click here.

Send comments and feedback to Eric Black, our editor. For comments to be published, please specify “letter to the editor.” Maximum length for publication is 300 words.