The most delusional moment of my life occurred Nov. 4, 2008. For an hour or so after Barack Obama won the U.S. presidential election, I believed the worst of America’s racism had subsided. America elected a black president. Surely, we must have “arrived.”

What a foolish thought.

Since that historic moment, racism has resurged. Sure, legislative and judicial remedies remain on the books. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 remains law, and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 is partially intact. States, schools, businesses and other public institutions retain policies that demand civil and/or equitable behavior.

Editor Marv KnoxBut plain ol’ mean-spirited, small-minded, fear-filled racism rebounded.

Editor Marv KnoxBut plain ol’ mean-spirited, small-minded, fear-filled racism rebounded.

Much of it surrounds the presidency. That’s not a statement about President Obama’s performance or about principled differences between political parties. The president has endured opposition—certainly from his adversaries, but sometimes even from within his own party—never propelled against a president. If you don’t believe race plays a role, then read the comments sections of news websites. Or just pay attention to how people talk. You don’t have to listen long to hear people indict themselves.

The election of a black president let loose a deep, primordial fear in many Americans. The “other” is in control. Even some folks who thought they weren’t racist have behaved differently now that someone of another race holds the most powerful job in all the land.

Racism in the streets

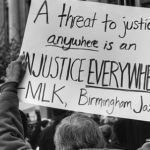

But racism isn’t all about politics and the White House and the first African-American president. It’s in the streets, too.

Most attention this summer has focused on Ferguson, Mo., where a white police officer, Darren Wilson, shot and killed a black teenager, Michael Brown. You know the story—lethal force applied to stop an unarmed 18-year-old. You’ve heard the conflicting accounts—Brown raise his hands up before five of six shots hit him, or he charged the officer he already had beaten. But still. Six shots—several in the head—to calm a teenager. Really?

Sign up for our weekly edition and get all our headlines in your inbox on Thursdays

You also know about the looting and the riots and the police in military gear. But is that really surprising in a town where 70 percent of the residents are black and 50 of 53 police are white?

Of course, we are a nation of laws. People should obey laws. Police should protect laws. Laws keep society civil.

Fairness and equal opportunity

But we also should be a nation of fairness and equal opportunity. On that score, we’re still missing the mark. Not just in Ferguson, but all across the country, the deck is stacked against people of color. Proportionately, their children attend worse schools. Many live in food deserts, where well-stocked, reasonably priced grocery stores are not present. Their communities offer fewer jobs and even fewer-still that provide decent wages. And young men of color get locked up all out of proportion to their numbers.

People who dismiss Ferguson’s rioting for thuggery are tone deaf. Communities don’t run rampant just because one kid died. And they don’t loot a convenience store just because the opportunity to rip off a carton of cigarettes and a case of soft drinks presented itself. If you listen to Ferguson’s chants, you hear more than rage. You hear disappointment and sadness and betrayal borne of the recognition many Americans don’t really believe all people are created equal. And that means them.

Of course, Ferguson does not stand alone. It’s just the latest flash point. Next week, next month, next year—and multiple points in-between—our attention will fix upon other stories of other travesties.

What are we going to do?

So, what are we going to do about it? People of goodwill should stand together—crossing racial, ethnic, religious and party lines—to advocate for basic advances. They include:

• Better education. We must improve the schools in low-income neighborhoods. Of course, that’s complicated and depends upon parental and community involvement as well as money and educators. But we also can provide incentives for the best teachers to teach in the most challenging schools. Also, we need to teach practical job skills for the global marketplace, so children who do not go to college are prepared to earn a decent living.

• Fair wages. We must raise the minimum wage. At the very least, wages should be high enough so a family of two parents raising two children can live above the poverty line if they both hold down full-time jobs.

• Jobs. Companies should be encouraged to keep manufacturing jobs at home. They also should receive incentives to place many of those jobs in low-income and nonwhite communities and neighborhoods.

• Family support. We must structure tax laws to encourage keeping families intact. We also must secure safe, affordable childcare so parents can work to support their families.

• Judicial reform. Our country is warehousing young men of color for committing nonviolent crimes, mostly involving drugs. This is counterproductive on multiple levels. It undermines families, costs money, erodes the labor pool and ruins lives.

Beyond this, Christians live under Jesus’ mandate to minister to the people he called “the least”—the weak and vulnerable, the outsider, the outcast. We can—and must—do more to improve race relations in America.

We can start by supporting education, jobs training and economic development. Churches—the richest pool of human resources in our nation—can impact all those variables if we work cooperatively, strategically and tactically.

But churches also can make a singular contribution to race relations if we provide a safe place to talk. A huge factor in our fractured society is our failure to hear each other. What if church became a place for people of various races came to listen—nondefensively, receptively, respectfully?

Words can stop a bullet if they prevent it from being fired in the first place.

We seek to connect God’s story and God’s people around the world. To learn more about God’s story, click here.

Send comments and feedback to Eric Black, our editor. For comments to be published, please specify “letter to the editor.” Maximum length for publication is 300 words.