It was the second phone call that did it. The first call got my attention and started the adrenaline flowing, but it was the second call that changed my life forever.

Around 8 p.m. on Apr. 17, 2013, my deacon called me. He knew I was out of town that evening; so, he needed to let me know the fertilizer plant in our hometown of West had exploded.

I told him we were on our way home, and as soon as we could get there, I would make sure the dog was all right and then do everything I could do to help. We hung up, and he called back almost immediately.

“John,” he said, “you don’t understand. You don’t have a home to go to, and you probably don’t have a dog.”

I hung up the phone, and my life was never the same again.

Ours was a major disaster that destroyed or severely damaged half of our town. We lost 15 people that night, and many others were injured badly. My community was changed forever.

That’s what disasters do. They change the community and each person affected.

Our current pandemic is a disaster that dramatically will change our lives and will change our culture forever. Most of us will get through this, and we will work together to rebuild our world, but things will not be the same.

Someday, we will be able to establish a “new normal” and move on together. That phrase—“new normal”—is a meaningful and powerful phrase when used appropriately, but it can be unhelpful and even harmful when used recklessly.

Sign up for our weekly edition and get all our headlines in your inbox on Thursdays

Although we often hear “new normal” used by the media these days, it is not a good idea for us to use that phrase to describe our current experience of social distancing or quarantine. There will be a time to settle into a “new normal,” but that time has not yet come.

The disaster pattern

While every disaster is unique, they all follow a set pattern, and the communities’ responses generally can be tracked in similar ways.

The familiar pattern of disasters consists of three phases: rescue, relief and recovery.

Rescue

Rescue is the initial phase. Immediately following a catastrophic event, there are efforts to rescue those who are injured or trapped. The priorities in this phase are first aid and life-saving measures. The rescue phase typically lasts for hours or days.

Relief

During the relief phase, volunteers, charitable organizations and trained responders like Texas Baptist Men help those who were affected directly to get what they need to survive. The priorities in this phase are food, clothes and shelter. Relief can last for days or weeks.

Recovery

Finally, the disaster survivors move into the recovery phase. While the first phrase is immediate, and the second is short-term, the recovery phase is long-term. It can take months or years. During recovery, the priorities are rebuilding, reconnecting, grief support and healing.

The COVID-19 disaster is very different than most, but as we go through it, we will experience all three phases. Since the initial event is unfolding so slowly, the significant difference is the three phases will be stretched out and will overlap.

Most disasters happen quickly. The storm comes in, the floods rise, the fires spread, the explosion happens. In our current disaster, the event itself is taking months to occur. That means we are still in the rescue phase, while the relief phase already has begun.

The nature of life-changing events

Major life-changing events happen in two ways. They can be characterized by bumper cars at the fair or a big ship on the ocean.

When I was a child, my favorite ride at the fair was the bumper cars. I never knew what would happen once the power was turned on and we all started moving. I could be going in one direction, and suddenly someone would hit me from the side, and I was headed in a whole new direction. That is the way life usually changes in disasters. It is immediate and often unexpected.

There are changes in life, however, that happen more like redirecting a big ship in the ocean. A maneuver like that cannot happen quickly but must happen gradually over time.

The COVID-19 disaster is like the big ship. Our lives are changing, we cannot stop it, and it is a slow and steady change.

Since the catastrophic event is slow in occurring, the first and second phase of the disaster are rolling out slowly before us, and they are beginning to overlap.

Why social distancing isn’t the “new normal”

It is important to stress: We have not yet entered the recovery phase. That phase cannot begin until the immediate danger of the virus has passed and the appropriate officials have announced an end to the quarantines and “stay-at-home” orders. That will be the time to encourage one another with the hope found in a “new normal.”

We must not describe our isolation as the “new normal,” because that will cause it to have the opposite affect it should have. If being alone, isolated, uncertain and frustrated is a “new normal,” where is our hope?

Instead, we need to see this time as the relief stage of a disaster. We are working together and trusting our leaders to get us through and to ensure as many people as possible survive. This is not normal, and it should never be considered as such.

Emotional responses to disasters

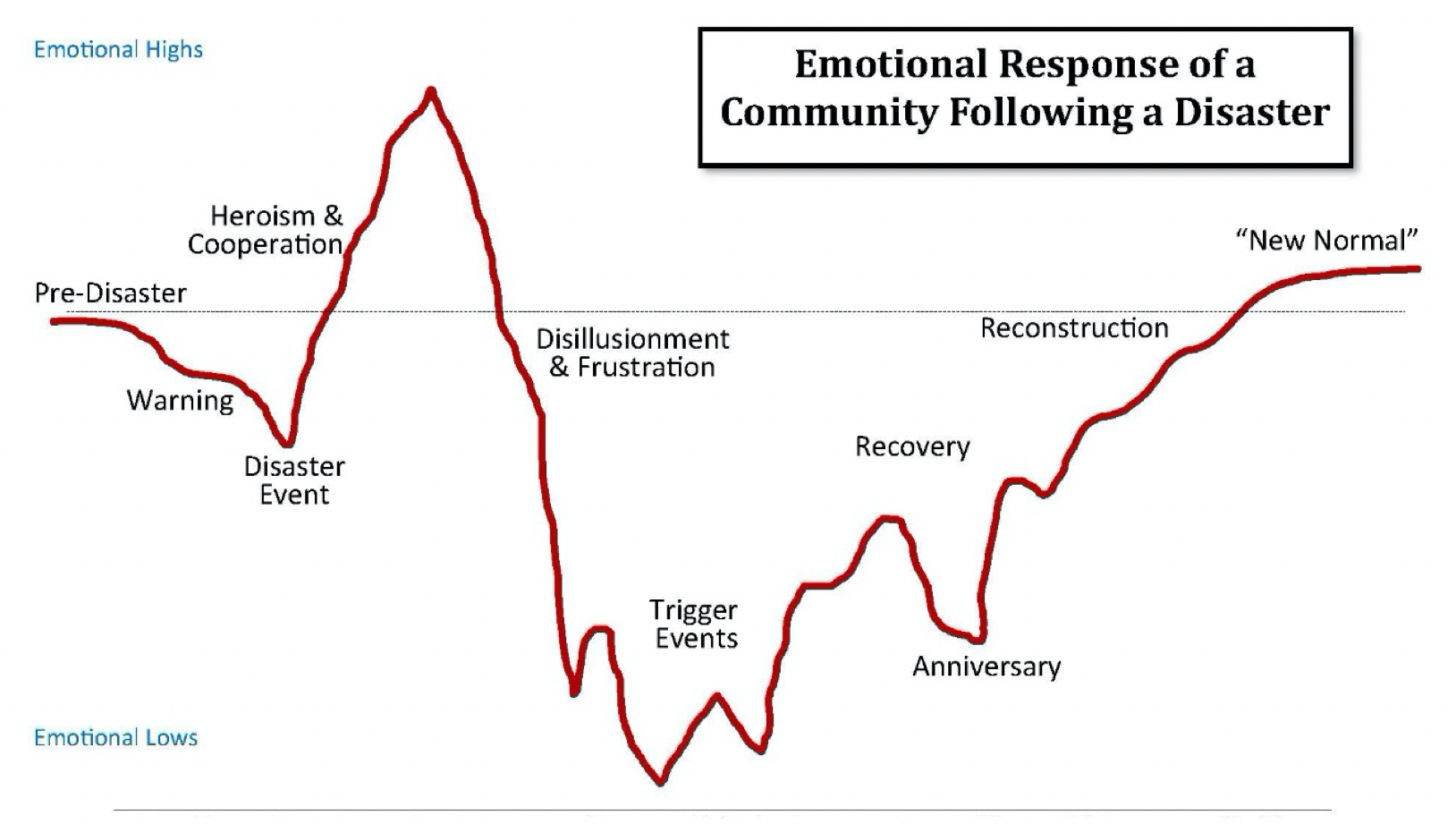

Just as most disasters follow a set pattern of three phases, the emotional responses of affected communities can be tracked in similar ways. Those responses are best demonstrated in a graph published jointly by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and the Federal Emergency Management Agency of the U.S. Department of Homeland Security. More information about the graph is available here and here.

Human Services and the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) of the U. S. Department of Homeland Security.

It is important to note the graph only represents the emotional response of the community. It is not intended to address economic, political or physical aspects of recovery. Nor does it speak to the experience of an individual who suffers a great loss in a disaster. It only represents the corporate, emotional experience of a community.

Emotionally, the highest point is soon after the event as people work together, help each other and celebrate the “heroes” who stepped up or showed up to help.

We currently are moving up that ascent as we encourage one another to, “Stay home, and stay strong.” We see it also in our newly discovered but well-deserved appreciation for heroes like medical professionals, grocers, delivery people and teachers, among others.

All too soon, we will turn the corner at the top and begin rapid decline as we become disillusioned and frustrated. We will see terrible division again as people start finding blame, pointing fingers, expressing anger and making demands. That will not be a good time for us, and it is precisely because of that part of the recovery process that we must not speak of a “new normal” too early.

Being truthful about a long recovery

People need to know this is bad, but we will get through it if we continue to work together. We do not want inadvertently to send a message that people should get comfortable in a state of emotional decline. We need to provide hope things will get better. This is not normal. It is anything but normal, and we must not settle in here.

As a community begins emotional healing and recovery, the line on the graph starts moving upward again. There are certainly “ups and downs” along the way, but it is generally moving upward. The community is making progress. During that time, we want to point out and celebrate every accomplishment. We can encourage one another to keep up the hard work, because we are improving, and progress is success.

Eventually, we will get through this disastrous time. Judging by the slow-moving nature of the current crisis, we cannot expect to get to the end of the graph very quickly, but we will get there. And notice, once a community arrives at the end of recovery, the emotional response of that community is generally higher than it was before the disaster hit.

Immediately following a disaster, we often hear civic leaders tell their communities, “We will rebuild, and we will be better and stronger than ever.” As the graphs shows, that is not just political rhetoric. Communities who go through disasters and complete their recovery usually are stronger and emotionally healthier than they were before the disaster. We can expect that to be our experience, as well.

One of these days we will get through this. God has always been faithful to us, and he once again will guide us faithfully through this dark time.

When we come out on the other side of the valley, we will see life is good, and we will be stronger people for having worked together when we needed each other the most.

Then, we can welcome people to their “new normal” that will be stronger, more hopeful, more appreciative and less selfish than it was when we started this long journey.

Until we get there, let us live out the three simple steps to enduring hard times found in Romans 12:12—“Rejoice in hope, be patient in tribulation, be constant in prayer” (ESV).

John Crowder is pastor of First Baptist Church in West.

We seek to connect God’s story and God’s people around the world. To learn more about God’s story, click here.

Send comments and feedback to Eric Black, our editor. For comments to be published, please specify “letter to the editor.” Maximum length for publication is 300 words.